| Steelers 35, Cowboys 31 |

|

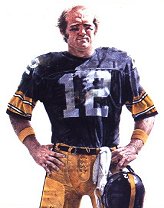

January 21, 1979 As the Pittsburgh Steelers were rehearsing for Super Bowl XIII, somebody recalled the day when Terry Bradshaw, asked what he thought about Rhodes Scholars, resorted to a costly bit of humor and replied: "I never did care for hitch-hikers." The remark backfired on the Pittsburgh quarterback. To many, it was seen as further evidence that Bradshaw lacked gray matter beneath his rapidly receding blond hairline. Even after he had led the Steelers to Super Bowl championships in 1975 and '76, the 6-3 Louisianian with a soul for country and western pathos was unable to shake the evil rap. Any compliments directed toward the quarterback usually were accompanied by, "Yes, but ...," alluding to alleged mental deficiencies. Bradshaw rarely, if ever, offered disclaimers, although he once declared, "I'm not extremely brilliant and have never claimed to be, but I can study a tendency chart on the defense and select the plays that will work in a given situation. This isn't nuclear physics, it's a game. How smart do you have to be?" Thomas Henderson, the loquacious Dallas linebacker who had christened himself "Hollywood" in recognition of his showmanship, used the word "dumb" in describing Bradshaw during Super Bowl week. The game, proclaimed Henderson, belonged to the team with the Texas-size IQs. Bradshaw, he said, couldn't spell "cat" if "you spotted him the "c" and the "a". In the early evening of January 21, 1979, the son of the Louisiana soil sat in the locker room beneath Miami's Orange Bowl, spitting tobacco juice into a paper cup. Bradshaw jokingly ordered newsmen clustered about him, "Go and ask Henderson if I was dumb today." Nobody stirred. The inference was clear. This day belonged to Bradshaw, named the Most Valuable Player in the Steelers' 35-31 victory over the Dallas Cowboys before a crowd of 79,484. Bradshaw had completed 17 of 30 passes for a record 318 yards and passed for four touchdowns, another Super Bowl record. Bradshaw had to be brilliant because the Steelers' ground attack netted only 66 yards against the Doomsday II defense of the Cowboys. While Bradshaw was hurling zingers at Henderson, the linebacker slumped dejectedly in the Dallas clubhouse, trying unsuccessfully to stem tears with a bravado that fell short of the mark. "I'm a little sad," he confessed. "I didn't feel defeat until the game was over. Now I'm upset. I was working out there. Now I'm on the verge of a heart attack. I'm hurt that we lost. I'm hurt that I didn't make the big play to win the game." Did Hollywood still question Bradshaw's intelligence? "I never questioned his ability," he responded, neatly sidestepping the issue. Crushed as he was by his own shortcomings and the Cowboys' defeat, Henderson probably was crushed even more by a putdown by Joe Greene, the Steelers' defensive tackle, during the game. After a Cowboys kickoff sailed out of bounds and the teams were returning upfield, Greene sauntered off the sideline to inquire of Henderson: "What is a superstar like you doing on a kickoff team?" Hollywood's puff was coming home to roost. The Steelers' route to a third Super Bowl was marred by only two defeats. They suffered a 24-17 loss to Houston and a 10-7 setback at the hands of Los Angeles, after which they ran off seven consecutive victories -- climaxed by a 33-10 thumping of Denver in the divisional playoff and a 34-5 whipping of Houston in the AFC title game. The Cowboys started the season sluggishly, winning only six of their first 10 games. Roger Staubach attributed the unimpressive record to "the Super Bowl syndrome, just not giving it everything you've got." The quarterback said the team was inconsistent, as if each player was waiting for another to do something to end the slump. The quarterback did not absolve himself from blame, pointing to his numerous interceptions. Running back Tony Dorsett was fumbling too frequently, Staubach said, while the offense and defense took turns playing ineffectively. Suddenly, however, the Cowboys found the combination for success. The various units started to mesh. After a 23-16 reversal by Miami, the Cowboys won their last eight games. Included were a 27-20 decision over Atlanta in the divisional playoff and a 28-0 whitewash of Los Angeles in the NFC championship game. In the rout of the Rams', Staubach passed for two touchdowns and the Dallas defense made five interceptions, including one by Henderson that was converted into a 68-yard TD gallop -- finished off with Hollywood's patented slam-dunk over the crossbar. Dallas' defense was the most stubborn in the NFC, allowing only 107.6 rushing yards per game. Pittsburgh's Steel Curtain was the stingiest in the AFC, permitting an average of 107.8 yards rushing per game. "The first Super Bowl rematch (Pittsburgh won, 21-17, in Super Bowl X) was the game that everybody's been waiting for," said Dallas defensive end Harvey Martin. Teammate Ed (Too Tall) Jones thought that the key to the contest would be the Cowboys' degree of success in controlling Bradshaw. "If we do that well," he said, "we've got a good part of the battle won." Greene predicted that the winning team "will be the most successful at getting at the quarterback." Dallas Coach Tom Landry predicted that the champion would be the team that scored 21 points, a total achieved 12 times by each team during the season. As a fitting tribute to one of the NFL cofounders in 1920, the pre-game coin toss was conducted by George Halas. The legendary coach of the Chicago Bears -- and now the club's board chairman -- was transported in an antique car to midfield, where he made the ceremonial flip with an 1820 gold piece for the captains of the two teams. Calling the toss correctly, the Cowboys received the opening kickoff and launched an impressive drive, looking every inch the team that had accumulated 5,959 total yards during the season. With Dorsett ripping off huge gains, the Cowboys registered two quick first downs in moving from their 35-yard line to the Steelers 34. On a first-and-10, however, wide receiver Drew Pearson fumbled a handoff from Dorsett on a double reverse and John Banaszak recovered for the Steelers on their 47. The play, on which Pearson was to have thrown to tight end Billy Joe DuPree, was relatively new to the Cowboys, having been installed before the conference title game against Los Angeles. Lamented Pearson: "We practiced that play for three weeks. It is designed for me to hit Billy Joe 15 to 17 yards downfield. We practiced the play so much it was unbelievable we could fumble it. I expected the handoff a bit lower, but I should have had it. Billy Joe was in the process of breaking into the clear when the fumble occurred." Six plays and two first downs after the fumble, the Steelers were on the Dallas 28, from where Bradshaw passed to wide receiver John Stallworth in the corner of the end zone for the game's first touchdown. When Roy Gerela converted, the Steelers had a 7-0 lead with 5:13 gone. "We exploited a Cowboy weakness we spotted on film," explained Stallworth. "We saw the cornerbacks jumping around, so I took a slant, then cut back to the outside and Terry lobbed the ball to me." The Cowboys failed to reach their 40 on either of their next two possessions, but with one minute remaining in the quarter, Harvey Martin sacked Bradshaw -- who fumbled -- and Ed Jones recovered on the Pittsburgh 41. After a two-yard gain by Robert Newhouse and an incomplete pass, Staubach found Tony Hill uncovered on the 26-yard line. Time was running out as the wide receiver tightroped the sideline for the equalizing TD. It was the initial first-quarter touchdown scored against the Steelers in the season. After one period the teams were not only deadlocked in points, but also were virtually equal in other statistics as well. The Cowboys held a running edge, 36 yards to 23, while the Steelers excelled in passing yardage, 83 to 63, and in first downs, five to four. With less than three minutes elapsed in the second quarter, the hard-charging Cowboys forced a second fumble by Bradshaw. On the Pittsburgh 37, Bradshaw was stripped of the football by Henderson and linebacker Mike Hegman picked up the football and raced in for the touchdown. Rafael Septien's second conversion sent the Cowboys in front, 14-7. The Dallas edge endured less than two minutes, or until Bradshaw connected again with Stallworth. From his 25, Bradshaw passed to the wide receiver on the 35. Stallworth broke a tackle by cornerback Aaron Kyle and cut toward the middle of the field to complete a 75-yard pass-run play. Gerela knotted the score a second time, 14-14. Kyle offered no excuses for failing to stop Stallworth. "I just missed him," he said. "If I had been in a better position initially, maybe I would have stopped him. Pittsburgh has two good outside receivers, but we are paid to cover them. If we don't do it well, we get beat. They get paid to catch the ball, we get paid to cover them." Stallworth was not the primary receiver on the play, Bradshaw disclosed. "I was going to Lynn Swann on the post," he said, "but the Cowboys covered Swann and left Stallworth open. I laid the ball out there and it should have gone for about 15 yards, but Stallworth broke the tackle and went all the way." On their subsequent possession, the Cowboys were in their two-minute drill and had reached the Pittsburgh 32 when a Staubach pass intended for Drew Pearson was intercepted by Mel Blount. When Staubach returned to the bench, saddled with his only interception of the game, as events proved, Landry asked, "Why didn't you throw late to Billy Joe (DuPree)?" "Why did you call that play? It's ridiculous," Staubach shot back. "We have a two-minute offense. Why were we running that play?" Landry reasoned that the play had been successful against Pittsburgh in the past, including Super Bowl X. Staubach figured that overuse of the play-action pass would breed familiarity among the Steelers defenders. The element of surprise would be gone. Had Blount been playing his position properly, he should have been up short, Staubach concluded, not back where he could make the interception. "Of all the passes I've ever thrown," noted Roger, "this one will haunt me the longest." After making the interception, Blount returned the ball 13 yards to the 29. A holding penalty set the Steelers back 10 yards, but Bradshaw put the club on the march again. Two passes to Swann put the Steelers on the Dallas 16 and, at 0:40, Franco Harris picked up nine yards against the left side. The clock showed 0:33 when Bradshaw, from the Dallas 7, arched a soft pass toward the right side of the end zone. When Rocky Bleier pulled in the pass and Gerela converted, the Steelers had a 21-14 halftime lead. Halftime statistics strongly favored the Steelers. The AFC champions led in first downs, 13 to 7; net yards passing, 229 to 61, and net yards, 271 to 102. Only in net yards rushing (42 to 41, Steelers), were the Cowboys compatible. Septien's 27-yard field goal with less than three minutes remaining represented all the scoring in the third period, but Dallas barely missed a touchdown that would have given the Cowboys a tie after three quarters. The unfortunate player in the near miss was Jackie Smith, 38-year-old tight end who had retired from the St. Louis Cardinals after the previous season when a doctor informed him that a neck condition threatened paralysis if he continued to play. When the Cowboys needed a backup tight end and made a pitch for his services, Smith consented, but only if he was able to pass the physical. Jackie surmounted that obstacle and throughout Super Bowl week had cavorted like a young colt, declaring, "I'm a very happy, fortunate old man, particularly when I think of all my old teammates who never made it to the Super Bowl." Now, with time running out in the third period, and on a third-and-three on the Pittsburgh 10, Staubach passed to Smith, alone in the end zone, but the hands that once caught everything they touched dropped the football. "That wasn't exactly the way we had worked on it," acknowledged Smith. "It was a good call, I just missed it. I slipped a little, but still should have caught it. I've dropped passes before, but never any that was so important. "Maybe I should have tried to catch it with my hands only, but in that situation you try to use your chest. Then I lost my footing, my feet ended up in front of me and I think the ball went off my hip. It's hard to remember, those things happen so quickly." Attempting to take some of the heat off Smith, Staubach said, "When I started to throw, there was no question in my mind, I knew the pass would be completed. But it wasn't a good throw. I took too much off it. If you're casting blame, it's 50 percent my fault and 50 percent Jackie's. I know one thing, the play wasn't a failure for lack of experience because we're the two oldest guys on the team. "One call, one play doesn't make a game. The Steelers' defense made some key plays." One of the key plays occurred early in the fourth quarter and set that period apart from any of the previous 51 Super Bowl quarters as a spawning ground for controversy. The source of the long and loud dispute was a bumping incident between Lynn Swann of the Steelers and cornerback Benny Barnes of the Cowboys. From his 44-yard line, Bradshaw passed to the right where Swann and Barnes collided and fell to the turf as the ball rolled free. Back judge Pat Knight, standing nearby and with an unobstructed view of the play, spotted no infraction. Field judge Fred Swearingen, a 19-year veteran of NFL officiating and observing the play from a considerably greater distance than Knight, called a tripping violation on Barnes and quickly the ball was on the Dallas 23. Shrieks of protest rose from the Dallas bench. "He missed it," said Landry, referring to Swearingen. "Because the safety blitz was on, all Bradshaw did was throw up an alley-oop pass, hoping Swann could run under it. Benny had taken away the inside because of the blitz (keeping Swann away from the area vacated by safety Cliff Harris) and was running with Swann when he looked back to locate he ball. The ball was inside him so Swann cut across trying to get to the ball. "He cut across the back of Benny's legs, tripped and fell down. Benny was tripped, of course, and fell. "When he hit the ground with his chest, his feet flopped up. That's the only thing that Swearingen could have seen. He assumed after the play that Benny tripped Swann." Landry added, "But Knight was there, just a few feet away on Benny's side looking at the play. He called it a good play and should have argued for Benny because it was so obvious from his side. Normally, one official won't go against another's flag, but I think Knight should have done so in such a big game. "Swearingen had no idea what had happened. He had Swann between him and Benny. He just saw Benny's feet flopping up and to him that was a tripping move. Swann was the one who did the tripping, when he cut across Benny's legs." Barnes' version of the play was as follows: "Swann ran right up my back. When I saw the flag I knew it was on him. I couldn't believe the call. Maybe Swearingen needs glasses, maybe he's from Pittsburgh. "I don't even know how far behind me Swann was. Then I felt hands on me, then he tripped me. The ball was catchable between us. I had the right of way, I'm told. The ball was just floating up there. "The official said I swung my foot back to trip Swann. I didn't even see Swann." Not unexpectedly, Pittsburgh opinions coincided with that of Swearingen. "I didn't think there was anything controversial about the call," reported Swann. "I was tripped. I didn't see Barnes and didn't touch him. My hands are clean. I'm one of the good guys." "There was a safety blitz and no pickup and I knew it," explained Bradshaw. "So I put the 'Hail Mary' on the ball. It was a good call by the official." Swearingen, a Carlsbad, Calif., real estate broker, defended his call. "It was a judgment call," he explained. "The players bumped before the ball was even close to them, perhaps before the ball was thrown. They were both looking back and the defender went to the ground. The Pittsburgh receiver, in trying to get to the ball, was tripped by the defender's feet. He interfered with the receiver trying to get to the ball. It was coming to him in that direction and I threw the flag for pass interference." Knight, a San Antonio lumber firm executive whose initial call of an incomplete pass was overruled by Swearingen, said, "I was about seven or eight yards from the play and had about a 10-degree angle. Fred's angle was a little different. We think it was a good call." From the Dallas 23, the Steelers advanced to the 17, then were set back to the 22, from where Franco Harris broke over the left side for a touchdown, climaxing an eight-play, 84-yard drive. "I was expecting a blitz," reported Bradshaw, "so I called for a quick off-tackle trap. You blitz on that play and Franco will bust it." The Steelers now led 28-17 -- a lead that ballooned by seven more points in less than a minute, largely because Randy White fumbled the ensuing kickoff. The All-Pro defensive tackle of the Cowboys was wearing a cast to cover a fractured right thumb and was stationed in the middle of the field to lead the blocking charge for the kickoff return. Chances of the kickoff going to White were extremely small, except that in this instance it did. White fumbled when tackled by Tony Dungy -- and Dennis (Dirt) Winston recovered for Pittsburgh on the Dallas 18 with 6:57 remaining. Roy Gerela had not intended that the kickoff should go to White. "I thought I'd kick the ball into the end zone and they would down it and bring the ball out to the 20-yard line," he said. "But the field has a sandy base. My foot slipped as I approached the ball. It wasn't the kickoff I wanted, but it worked out to our advantage." "We had it planned that if the kick was squibbed, we would lateral it back to one of the deep backs," explained White. "But it took me so long just to pick up the ball, I had to go with it. When I started running, I fumbled the ball, that's all there was to it. I've handled a couple of kicks this year, but I fumbled this one." On the next play, Swan caught Bradshaw's 18-yard pass on the rear line of the end zone and Gerela's fifth extra point gave the Steelers a 35-17 cushion. On the Pittsburgh bench, general merriment alarmed Bradshaw. "With more than six minutes left, our guys were celebrating," said Terry. "That made me mad because I remembered the Super Bowl three years ago when Dallas came back and threatened to pull it out. "1 looked out on the field and here was Roger scrambling well, throwing well, moving them downfield and they scored twice. I got very upset. We had scored 35 points on a team that seldom gives up that much and then it looked as though we might wind up losing it. "And here were our fellows on the sidelines shaking hands and slapping one another on the back." Jack Lambert was worried, too. "Fortunately," said the Steelers' middle linebacker, "we had a large enough lead so that the Cowboys' comeback didn't affect us." The Dallas comeback commenced immediately after the kickoff. In eight plays the Cowboys marched 89 yards, with Staubach passing the last seven yards to DuPree. When Septien converted, 2:27 showed on the stadium clock and it was 35-24. Septien's onside kickoff was bobbled by the Steelers' Dungy and recovered by Dennis Thurman of the Cowboys on the Dallas 48. In nine plays -- eight passes and a sack -- the Cowboys scored again. Staubach's four-yard pass to Butch Johnson produced the TD and Septien's extra point lifted the Cowboys within four points of the Steelers, at 35-31, with 22 seconds remaining. As the Cowboys lined up for what was certain to be another onside kick, sure-handed running back Rocky Bleier waited on the Dallas 45-yard line, reflecting on his chances if the football came to him. "I was trying to anticipate what Septien would do," said Bleier. "If he kicked it hard and tried to bounce it off me, I was going to let it go through to Sidney Thornton rather than risk a fumble. But he decided to dribble the ball and it wasn't that hard, so I was able to get under it, and I was relieved." Twice, Bradshaw took the snap and fell to the ground as time expired. The once ragtag Steelers, the poor relations of the National Football League, were the first team to win three Super Bowls. Postgame paeans rang loud and clear for Bradshaw, selected the MVP. "He throws a football 20 yards like I throw a dart 15 feet," praised Charlie Waters, Dallas safety. "Every time we got them in a third-and-eight situation, Bradshaw would throw another unbelievable pass," observed Dallas' White. Bradshaw beamed over his record passing performance (318 yards and four TDs). "This sure was a lot of fun," he said. "I played this game just the way I hoped I would. "The thing I didn't want to do was change the things that got us here. Play-action passes, throwing the ball, doing whatever it took to win, that was what made this team. We just needed to keep it up. "I didn't want to come here and let the pressure of the Super Bowl dictate to me like it had dictated to some people in the past. I wanted to play my game, win or lose, and not give a hoot. I was surprised how relaxed I was. I was able to stay relaxed and not worry. "When I left this stadium, I wanted to know I had done what I needed to do." Swann admired the quarterback's play selection and confidence. "You couldn't ask for a finer quarterback or leader than Terry was today," said the wide receiver. "He had us tuned to just the right pitch." The Steelers' game plan, according to Swann, was to "throw to our wide receivers so Dallas' cornerbacks would have to make the tackles. The cornerbacks don't tackle as well as the safeties." Cliff Harris, one of the safeties (Charlie Waters was the other), had announced during the week that he planned "to hit Swann hard, not to hurt him, but that doesn't mean he might not get hurt." Was the blast he received from Harris along the sideline early in the game unnecessarily rough? Swann was asked. "That was a good clean shot to the chest," declared Swann, "and, anyhow, all that talk during the week . . . I'm at the point now, in my mind, where I could blast every Cowboy player who talked about me. But I prefer to let the results speak for themselves." Nobody agonized more over the Dallas defeat than Landry. "We tried hard, but we didn't take advantage of the opportunities we had," lamented the losing coach. "I said all along that turnovers and breaks would determine the winner. That's what happened today. On any given day the Steelers are no better than we are." Landry was not alone in his opinion. "My teammates may not like this," said Pittsburgh defensive captain Greene, "but the Cowboys are good enough that on any given Sunday they might beat us." "I'll think a lot about Bradshaw during the offseason," said Waters. "Unfortunately, the pain will get worse before it gets better." | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Page created by McMillen and Wife.